As this occasional blog may indicate, I am far more technophile than technophobe. Indeed, I prefer to embrace titles like “technophile” and “early-adopter”(^1) to stave off alternate images that would align my behavior with addictions — a case of Star Trek’s holodiction writ small — or as an embracing of wish fulfillment/delusions of grandeur of my being a superhero like Batman, with his voice controlled Batmobile and other wonderful toys, or Tony Stark with his computer assistant Jeeves.

I can stop any time. Really.

My predilection for technology has led me to think about technology and its use in the classroom on more than one occasion. Indeed, a search of iTunes will yield four Summer Institutes(^2), generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, that I organized which focused on Technology and New Media within the academy. Most of my personal focus has been on how the small, incidental uses of technology can improve the life of a faculty member and the experience of students in the classroom rather than on large scale initiatives — how a service like Periscope, for example, can come to your aid when you have to stay home with a sick child as opposed to an analysis of how to roll out online learning campus-wide for all faculty and students. I know people who do the latter (and try to work closely with them) and respect their work. It’s just that is not where my active interest currently lies.

As with all things, both levels of interest in ed-tech run the risk of losing sight of first causes — the underlying assumptions and needs that drive our decisions. Recently, it took me a surprising amount of effort to trace back to first causes my discomfort with a story that, when I read it, I thought I should be excited by. Union County Public Schools in North Carolina (I am pleased to say my daughter attends a school within this system.) published a piece well worth reading on how Vinson Covington, the AP European History Teacher at Parkwood High School, was getting his students to create a mobile app as a vehicle for learning about history.

Before I go any further, I want to make one thing clear. I think this is a fantastic, inventive idea and that Covington should be applauded for his work and for creating an environment where his students are engaged and are challenged to think about the subject differently. Nothing that follows should be seen as taking away from this, my personal and professional (for what little that is worth) assessment of what he is doing or take away from my hope that I see more teachers doing cross-disciplinary and interdisciplinary work like this at all levels of education. It is absolutely critical for all of our futures.

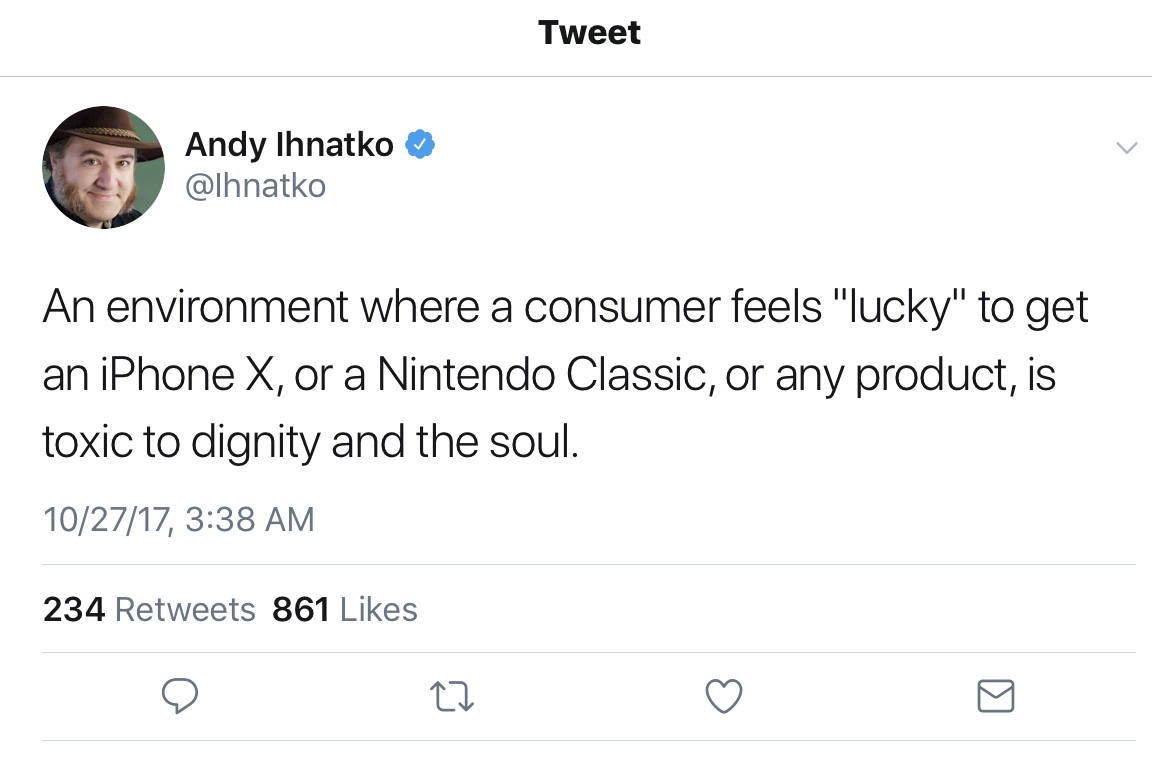

But as I was writing, I read this article and knew I should be interested an excited by it. Instead, I found myself disquieted. My first response to this disquiet, which I shared on Twitter, was that I would have felt better if it was part of a team-taught course, where the coding and the history could both be more fully explored by the students. And while I still think that, I no longer believe that is the source of my disquiet. Team taught courses are great but, from a staffing point of view, only occasionally practical. The kind of thing that Covington, on his own initiative, is doing here is a solution to a real zero-sum game that administration plays when trying to best deploy the limited manpower available.

Ultimately, I believe the source of my disquiet is the underlying assumptions about which disciplines should make space for others and how that space should be created. Those assumptions are building a hierarchy that many insist does not exist — even as they participate in building and reinforcing the hierarchy.

In Covington’s case, there is no sense — even in my mind — that it is wrong for history faculty to introduce a coding project into their classroom. Indeed, I remain in awe of what Mike Drout and Mark LeBlanc accomplished and continue to accomplish with their Lexomics Project and know that I need to find the time to use their tool to satisfy some of my own idle curiosities.

To illustrate my concern, consider how non-English and Language Arts faculty react when they decide that their students cannot write well. They turn to the English faculty and ask why they have not taught the students better and look to them to provide solutions. There is no perceived cultural pressure on the non-English faculties to introduce writing into their areas in the way there is to introduce coding into history, as in the case of Covington’s work.

And I hasten to point out that the kind of cultural pressure I am pointing out is not just negative pressure. Covington has been singled out for praise here for his innovation. Can you conceive of an article that praises a member of a Biology faculty for having Pre-Med students write sonnets to improve their writing and interpersonal skills? Can you see that article treating such assignments as anything other than silly? Or as a waste of time that would be better spent on the difficult subject matter material that students are perceived as needing to cover to succeed in medical school?

And yet, no one will deny that understanding how World War I started is easy or unimportant. After all, understanding a highly mechanized, semi-automated system of distributed but telegraphically linked command posts with a series of standing orders that, once begun, cannot be stopped without destroying the system (i.e., the Schlieffen Plan) might be analogous to our contemporary computer-controlled military systems might be what prevents World War III. And learning about sonnets and people’s emotional reactions to them might help a doctor have a better bedside manner or a sufficiently greater sympathy with a patient that lets them notice that, despite the glitter of their walk, their patient may need help. It might help those employed by insurance companies see less of the paperwork of procedure and more the people trapped within the system.

Innovation, then, must not be seen as a one to one correspondence with technology, science, and engineering. Innovation is when we take new ideas and apply them in any field. The unfortunate truth about the way we are currently recognizing innovation in the Academy is that we have tied it too closely to the use of technology — so closely that we can no longer see when innovation is taking place through other areas. This matters not just for humanities faculty who might fear they are becoming second-class citizens within their own disciplines. It also matters to faculty innovators like Brendan Kern, whose podcast on the life of an imagined exoplanet can teach students about biology through the exploration of an alien, new world. Such work is currently more likely to be advertised as “fun” or as a bit of fluff rather than a serious attempt at pedagogical development and innovation that might make material accessible to students.

Whether we in at all levels of the Academy choose to see innovation more broadly than the infusion of STEM and its wonderful toys into other disciplines will determine how likely we are to promote and recognize real innovation across all disciplines. It will require challenging many of our assumptions about how we do things and how much of a king our disciplinary content actually is. It will be difficult for many of us to do this. After all, it is easy to give the appearance of innovation if you see people working on robots or a flying car. It is less easy to do so when you watch someone telling or discussing a story. But both of these represent the skills our students will need to be successful and adaptable in the 21st Century. We must, then, learn how to refuse to be hidebound.

——

1. For those that are curious, I added the hyphen because of some research conducted by Sparrow Alden, who noticed that, in The Hobbit, J. R. R. Tolkien appeared to hyphenate certain two word phrases to indicate that they stood in for what would have been a single word in Westron (the common language of men and Hobbits in Middle Earth) and come down to us as kennings (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenning). Although early adopter is not traditionally hyphenated and is not as figurative as oar-steed or whale-road, it is nevertheless true that being called an early-adopter signals more than just being the first kid on the block with a new toy.

2. Or you could follow these links:

The First JCSU Faculty Summer Institute for Technology & New Media

The Second JCSU Faculty Summer Institute for Technology & New Media

The Third JCSU Faculty Summer Institute for Technology & New Media

The Fourth JCSU Faculty Summer Institute for Technology and New Media and Problem Solving in the Interdisciplinary Humanities